Symbolizing renewal in the ancient beliefs and resurrection in the Christian, fanesca is the traditional Easter dish in the Ecuadorian highlands.

photo © Lorraine Caputo

On Good Friday morning, doña Magdalena is stirring a large pot of broth. On a stove in the patio, her sister fries whole maduros (ripe plantains). At the kitchen table, doña Mariana guides grandchildren in making small empanadas. Doña Magdalena’s daughter tastes the picantes.

An essential part of the fanesca decoration is miniature empanadas and fritos (small, fried dough balls).

photo © Lorraine Caputo

During Semana Santa, this is a common scene in the kitchens in Ecuadorian highland homes and markets. Fanesca is an Easter Week tradition that brings families together. On Good Friday, generations gather to share this dish after the procession.

Dating from pre-Hispanic times, this heavy “soup” contains 12 grains and beans. Indigenous nations in these northern Andes prepared fanesca for the celebration of Mushuc Nina (Day of New Fire), observed on the March equinox and thus marking the beginning of a new cycle of life, a new year. The meal’s name in Quichua is uchucuta, meaning tender grains cooked with chili and herbs. It was possibly accompanied by cuy (guinea pig).

After the Spanish conquest, the new rulers attached Christian meanings to this traditional meal. In the Catholic iconography, the 12 grains and beans came to signify the 12 apostles and the 12 tribes of Israel. Dried cod (bacalao), representing Jesus, was added to the recipe as well as dairy.

Bacaloa – dried cod – was added to the recipe by the Spanish occupiers. In popular lore, it is said to represent Jesus. It is dredged in flour before being deep fried.

photo © Lorraine Caputo

Fanesca is a laborious meal to prepare. Just a generation ago, its elaboration would take several days. Each ingredient has its own treatment.

Some of the 12 grains and beans used to elaborate fanesca.

(Front to back, left to right) Frijol blanco, chocho, arveja, habas, melloco and choclo.

photo © Lorraine Caputo

The grains are meticulously soaked, cooked, peeled, and ground by hand (or with electric grinders and blenders in these modern times). The 12 grains and beans are: choclo (sweet corn), chocho (lupine beans), zapallo (a large winter squash similar to pumpkin or Hubbard), frijol blanco (white beans), habas (fava beans), zambo (another type of squash), arveja (peas), frijol rojo (red beans), maní (peanuts), garbanzo (chickpeas), mote (hominy), and melloco (a soft-fleshed tuber).

In the interim, the cream and codfish stock base is made. The grains are then added in a specified sequence.

Preparation of fanesca stock, which includes codfish, cream and a variety of herbs like garlic, parsley, oregano and cebolla blanca (Allium fistulosum, Welsh onion).

photo © Lorraine Caputo

Fanesca is served decorated with fried ripe plantain (maduro), cheese, hard-boiled eggs, mini cheese empanadas, strips of red chilies and parsley. Also on hand are several types of homemade hot sauces, including one made with zambo (squash) seeds.

Adornos (decorations) for the fanesca.

(Front to back, left to right) Cheese, squash-seed chili sauce, hot sauce, fritos (empanadas, dough balls). Hard boiled eggs; finely sliced red chili pepper, parsley, cebolla blanca; fried maduro (ripe plantain).

photo © Lorraine Caputo

The second course is molo: potatoes mashed with milk and perhaps a bit of lard or butter. It is served on a lettuce leaf and adorned with parsley, cebolla blanca and chunks of cheese.

The traditional desert course presented is cooked, sweetened figs with cheese, or arroz con leche (rice pudding).

¡Buen provecho!

Tips for Travellers

- If you don’t have an Ecuadorian family to invite you to the fanesca gathering, you may try this iconic dish in many restaurants (especially in the Centro Histórico of Quito). The stalls in the capital’s markets also serve up portions: Mercado Central (Avenida Pichincha and Manabí) and Mercado San Francisco (Calle Rocafuerte and Calle Chimborazo) are good places to try. Note: Many businesses are closed on Good Friday (Viernes Santo).

- Fanesca is a heavy dish. It is best to avoid eating it for dinner.

- Some establishments will give you the option of ordering it with or without the fish.

- Every year, Quito hosts a fanesca festival the week before and during Semana Santa.

Gracias a doña Magdalena y su familia, y la doña Mariana por invitarme a su mesa para aprender de la fanesca.

article and photos © Lorraine Caputo

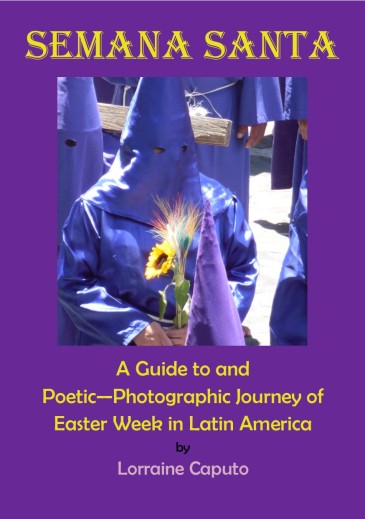

Get your free eBook guide to

Latin America’s Easter Week celebrations!

SEMANA SANTA : A Guide to and Poetic-Photographic Journey of Easter Week in Latin America

Last Sunday I had fanesca in Quito, and today friends served fanesca in Imbarra around 3 o’clock. At ten, I’m still stuffed from one bowl! My lean Ecuadorian friend took a second serving, though I don’t know where he managed to find room for it!

(I’m here thanks to Sara at Zero Latitude Living.) Great tutorial on fanesca. Thanks!

Lisa/Z

LikeLike

Thank you, Lisa, for your kind words.

For me, also, I find one bowl to be sufficient! It is true stick-to-your-ribs food!

LikeLike

Great history and explanation, thanks. I’ve been in Quito for the past 6 weeks and had the privilege to try a couple versions the past week. One, prepared in a typical and small comedor in my neighborhood near the Basilica, I liked a lot. The other, not so much. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you, Bob.

I, myself, have learned just how diverse recipes can be depending on the region the cook is from!

Doña Magdalena, who invited me into her kitchen to learn about how it is made, is from the Tulcán region (near the Colombia border). There melloco is part of the standard recipe.

But this weekend, I was invited to try fanesca made by a woman from Atuntaqui. I was surprised at how much creamier and lighter it was! One major difference, I was told, is the absence of the melloco.

It will be interesting to learn more about regional differences in the dish!

LikeLike

Pingback: SEMANA SANTA IN LATIN AMERICA : A Poetic – Photographic Journey – latin america wanderer

I have never heard of this dish, but it sounds AMAZING! Definitely on my list to try fanesca with guinea pig!

LikeLike

I’m not familiar with this dish, but it looks like something I would really enjoy. I’ll have to try the recipe out at some point!

LikeLike

This sounds a beautiful dish with or without fish…and cuy I would love to try this served locally…I love how food brings communities and families together with traditions

LikeLike

Looks delicious with lots of steps involved in the making.

LikeLike

How very interesting! We have many of the same foods in Cuban cuisine – maduros, etc – but I’ve never seen something like fanesca. I’d love to give it a try one day.

LikeLike

Great tips for trying fanesca!

LikeLike

Great description of this tradition. I love how cooking fanesca brings the families together.

LikeLike