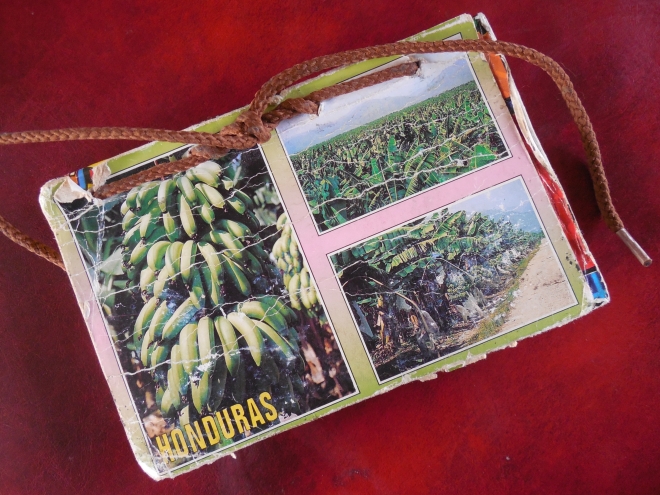

The complete manuscript of my works about the United and Standard Fruit Companies. photo © Lorraine Caputo

It’s a hot day in Omoa, Honduras. I stop at a refreshment kiosk on the road from the highway to the fort, and order a banana licuado. The small business belongs to María Elena’s family. She’s an English teacher. In front of her stacks her students’ exercises.

I tell her I’m writing a book about the banana companies. “I’d like to learn more about their history here. But there’s scant information. Not even the museum has much.”

She pushes those papers more to one side. Her hand is the color of maple. “My father remembers when they were here.”

I raise my eyebrows with an astonished smile. “Really? Several people have told me there’s no-one around here old enough to remember.”

María Elena bobs her head. The sunlight gleams on her dark hair. “Oh, yes. He remembers. Ah, the stories he’s told me about how duro, how hard it was. They weren’t paid in money, he says. Just in script.” She looks down at the pen in her hand. “I wish he would write it down—to preserve it for history.” She looks at me. “He’s a very respected man. Was mayor of Omoa for twelve years. Very popular. And he speaks a bit of English still. His father had sent him to boarding school in Belize.”

I swirl my straw. “Would it be possible for me to talk with him?”

“Sure. I’ll ask him. I’m certain he’d be delighted.” Her eyes dance. “And I’d love the opportunity.”

“Pues, perhaps you should bring along a tape recorder.”

She shakes her head. “I don’t have one. Just take good notes.”

I lay the empty glass on the counter and nod, you betcha.

º

Within the week, I meet Edmundo Riera Altamirano under the palm thatch of the stand. He is short and trim—hard to believe 82 years old. And his demeanor. He sits like a British (Honduran) schoolboy. Señor Riera slips into the occasional English with a smile and glint of eye.

“Of course I remember when he Company was here.”

María Elena serves us pineapple refresco, then joins us at a small table. I can tell by her eyes, she’s eager to hear her father weave tales.

“My father had eighty manzanas.” (I do a quick calculation in my head: that would be about 56 hectares.) This elder holds his tumbler with a café-con-leche-colored hand. “He grew bananas which he sold on exclusive contract to Cuyamel, and later to United Fruit. But after The Company left, he turned it into milpas and pasturelands. There’s much less of it now. Before he died, my father sold some off.”

I take a sip of the cool drink. It’s another scorcher of a day. “How was it then, don Edmundo?”

“Well, this was the main port. The railroad used to arrive to the wharf. Ships would pull up to either side to be loaded.” His eyes enter that time. “It was quite a sight.” He laughs.

Señor Riera word-paints the business of those days. The extent of Mr. Zemurray’s banana empire on this side of the Motagua River Valley. The giant racimos those fincas were famous for.

María leans forward, her chin on her hands. Her eyes are gleaming. She is riding his every image.

And I am transported back to that time. I can almost feel this town as it was then. The shouts of the bananeros. The train’s whistle as it rolled down this street. Wagons clattering by.

The sea used to lap against the walls of the forteleza. “I remember that so well as a child.” He glances down towards that old Spanish fortress.

It’s incredible it has receded so much in less than a century. El Suizo, the Swiss owner of the inn where I’m staying, explained to me it’s because of hurricanes and such. Señor Riera confirms this.

“Where was the old wharf?” I ask. It has long ago fallen into that bay. No, not even a timber is left.

María Elena looks at him quizzically. “That’s something I’ve never know, either.”

“Pues, you know where doña So-and-so lives? … No, no. That’s her cousin that lives in that white house …” And on and on daughter and father go, comparing local landmarks. My mind is trying to follow them. But it gets lost.

She turns to me, “You know the road that turns off for the gas company?”

I squint. “Yes, I’ve seen the sign. Right across from Bernie and Rollie’s place.”

“Well, just below there it was.”

Why The Company left. How it was afterwards. The lands were given back to the government—except those that were privately owned, of course. All that could be, was shipped out to La Lima—lock, stock … and rail. The banananeros received nothing but the houses. Many suffered. Only a few left to work on other fincas. “I did when I was 19, down to La Lima. For four years I washed fruit. I made my money and left.”

My pen poises. “And how was it back then?”

“Well. At that time the fruit arrived from the fields by mule. They didn’t have the cable system they do now.”

“Was it duro, tough?”

“Oh, sí. It was hard work, all right.” He takes a taste of his refresco.

“How was the pay?”

He sets his glass down. The condensation pools around his hand. “People were paid by hour of labor. For example, if it took three hours to load a ship, they got paid for three. If it took ten, they were paid for ten.”

“And how were the workers paid? In script, or …”

“Oh, no. In dollars, puros dólares. It was the only currency used here.”

I raise an eyebrow. “Not in script, or coupons for the Company store?”

Señor Riera shakes his head, thickly covered with white, close-cropped hair. “Oh, no. Dollars were king.”

I look at María Elena sitting next to me. She stutters a bit, “B-but, papa, I thought you’d told me …”

“Oh, no. In dollars.” He waves his hands. The subject is closed.

An Afro-Honduran pulls up a stump seat. Patches of light through the thatch gleam on his burnished-oak-colored skin. The father and daughter greet him. A refreshment is brought.

I drain the last of my drink. “Don Edmundo, is there anything left of those days? Houses, or …” I shrug.

The two men confer. Pues, sí, one executive’s house up in Cuyamel. That’s all.

The friend leans forward. “There is one locomotive here still. The Number Two.”

“Señor Riera nods. “It’s behind the museum.” He looks at the other, head atilt, with a bit of a smile. “A mere babe compared to the ones they took away.”

The Afro-Honduran closes his eyes. His skin folds thick. He moves his head slowly from side to side. “But, oh, is it in bad shape.”

María Elena puts her now-empty tumbler own. “Why don’t they put it inside? It should be preserved.”

The two oldsters wag their heads.

“It’s too heavy,” says the friend.

“Made of pure iron,” adds the elder Riera.

The other glances at him knowingly, “The real stuff.”

“What time do you have?” the father asks me, looking at the sun.

I pull my watch out of my pocket. “It’s almost five.”

He lays his broad hands on his knees. “Well, I’ve got to go tend the cows.”

The two men walk off, up towards the highway. María Elena says in a low voice, “I swear. Many times he has told me they were paid in script.”

º

Our conversation weaves through many topics. Finally, I notice the shadows of night have almost completely fallen. I should be getting back to my hotelito room down by the beach.

The light of the waning moon silhouettes the old fort. The gate in front of the museum is ajar….

º

º

published in

Flights (UK) (Issue 10, September 2023)