My search for a passenger train in Guatemala left me feeling like Doña Quixote.

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Resistencia, Argentina (a country where I did take a number of passenger trains).

photo © Lorraine Caputo

Once upon a time, I almost took a train.

No, I didn’t. And for many years thereafter I have waited, patiently, for the chance again.

I am defeated—or I choose to be. Here I put the Guatemalan iron horse out to pasture.

How many times I’d been in Guatemala over the years and never journeyed by rail: twice the end of 1988, twice the beginning of 1992; December 1993 and March 1994; and twice the beginning of 1996.

Now I sit here many years later, trying to figure out why I didn’t take it then, or even then. Sometimes my route north or south was in the wrong direction. Sometimes I was in too much of a hurry—sometimes others were. I believe one time I didn’t want to have to face the dangers of Guatemala City’s Zona 1 streets, hotel to station, at sunrise to catch a 7 a.m. train.

(Kick, kick, kick.)

In early 1992, I had met two young Dutch men. They told me of taking the train to Puerto Barrios. It was running so late, those small wooden cars skip-clicking through the pouring rain. Near Amate, the trip was aborted. A bridge had washed out. A woman they met aboard took them through the already-darkened streets to her home.

Their tale piqued my desire to someday take a chapín train. Images formed in my mind of narrow rails through jungle green, into the hearts of lives shielded from the highway view, into the banana plantations.

In November 1993, I began another trip to Central America. I vowed to take that train. So much for good intentions.

While at Lake Atitlán, I met an Israeli couple that wanted to do the Jungle Trail: a three-hour walk from Finca Chinoq, Guatemala, to Corinto, Honduras, through plantations and swamp. But they would like to have a translator. Would I be interested in coming along?

Need I think about it? For several years I had read about this. However, I had put my dreams aside, as a woman traveling alone. There’s no question. I’d be a fool…. Yes, I will.

We finalized our plans: a middle-of-the-night bus to Guatemala City, so they could take care of some business there. Then to the ruins of Quiriguá, and the next day head into the fincas. I suggested that we take the train. No: it is too slow; it is not the right day anyways; they want to get moving.

Well, when would I get another opportunity to do the Jungle Trail? And anyways, the train will always be there.

While the couple was off mailing a package in the City, I sat on the curb of the train station parking lot watching our gear. Sometimes I glanced over to the station, to the guarded gate into the railyards. The Jungle Trail versus a train. Is there a choice? And all along our bus ride to Quiriguá, I could occasionally glimpse those tracks. The Jungle Trail versus a train. Is there a choice?

Anyways, the train will always be there.

Well, in March 1996, the trains stopped. Sometime that same year the station in Guatemala City burned. I would see its empty hull and charred roof while passing through the capital.

Why did I never take it all those years?

Because, of course, it would always be there—it would never die.

Yeh, sure. Like chivalry and knights errant.

But hope was instilled in me.

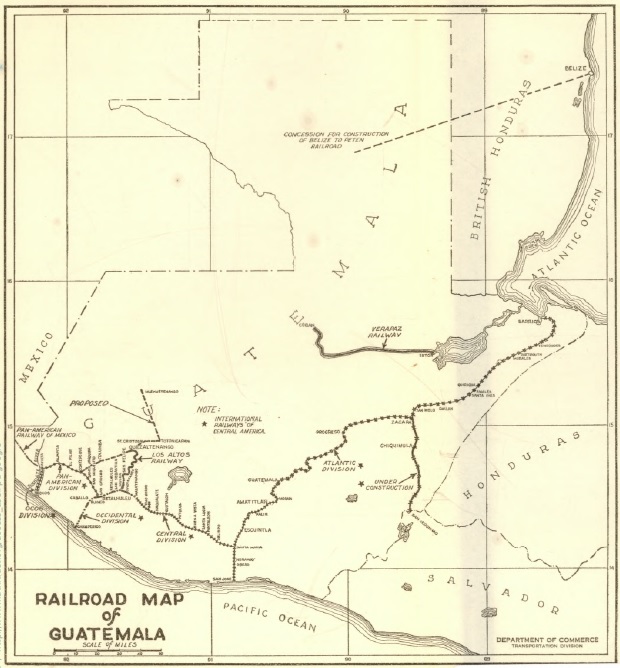

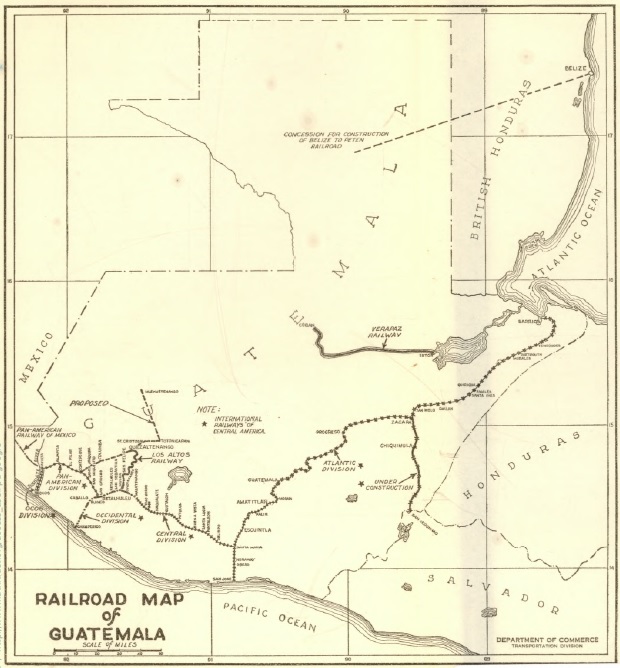

The railroads of Guatemala, 1925. from Wikipedia

In May 1997, I wrote to Ferrocarriles de Guatemala (FEGUA) to ask about the status of passenger services in its country. Within a month, FEGUA responded:

- Ferrocarriles de Guatemala suspended operations approximately one year ago, due to the very bad conditions of the infrastructure, for which reason the administration decided not to provide cargo nor passenger service.

- Presently, in the course of this month [June], it will be know who the new concessionaire of the rail system will be, based on offers submitted in previous months.

- [Such-and-such] company … in California … does excursions with steam engines approximately every year….

No, no special excursion trains. The purpose of riding the rails, of writing this book is to know the country. Not only the landscapes, but also that community that forms within the train. No, scratch number three—the community within will be foreigners, not Guatemalans.

Ah, but point two. A new concessionaire. So that means passenger service will return.

The end of that year, I hoisted my backpack Rocinante and headed into Latin America again. In February 1998, I arrived in Guatemala with a pocket full of that hope.

The stretches of rails I saw paralleling the highway from Tecún Umán on the Mexican border to Coatepeque appeared to be in good condition or under repair. Two Mormon missionaries in Ocós told me they had seen maintenance trains. But everyone I spoke with said the same thing: No, there are no passenger trains.

From Quetzaltenango I called the main office of FEGUA in the capital. Yes, a new administrator had been found, and passenger service will resume by the end of this year. There are no cargo trains running either. Rail reparations are underway.

Dang. Only about ten months too early.

For the next few months, the Guatemalan newspapers reported the struggles of the railroad to reclaim the clearance on either side of the tracks. In the less than three years since service was suspended, people had begun to build homes and businesses within that zone. Between Morales and Bananera I saw many market stalls and parking lots set up across the rails.

I guess, perhaps, Guatemalans has lost hope that the trains would ever return. I know I was beginning to—but held onto the Head of Transportation Department’s words: By the end of the year, there would be passenger service again.

Ay, and those tracks from Morales to Bananera to Quiriguá—in such horrendous condition.

10 March 1998 / Quiriguá

Rails heading into the banana plantation

split off just before the station

A few hundred feet down the line

a yellow & black gate blocks

with a simple word that shouts

ALTO

The old wooden station faded orange & black

rain gutters rusted through

138.3 miles to Guatemala City

59.1 miles to Puerto Barrios

Part is now a funeral home

even though a sign proclaims

PROPERTY OF FEGUA

Four children bounce on a low

fence made of a stretch

of an old rail

I stop to talk with a young man

in the former ticket office

& will this once more be a station

when service begins again?

He & his friend look surprised

But in Guate they say

by the end of the year

the trains will return

The friend says

Only God knows

A faded old-orange wooden boxcar

rots on its rusting wheels

The rusting rail upon rotten ties

becomes buried beneath

partly burned trash

weeds & fallen leaves

dirt eroded from a landscape cut

My heart quickens at the thought

of finally in the future

riding this train

I leave that stretch

at the turn-off for the highway

My Spirit wants to follow

its winding path

through tropical growth

those 59 miles to Puerto Barrios

In that port town, I spoke with the station chief. He was confident service would return.

That was before Hurricane Mitch hit in October 1998.

= = = = = = =

Again I begin planning another trip. I will give one last try at taking a train in Guatemala. In July 2002, I researched the internet. The new concessionaire is called Ferrovías Guatemala. Yes, it is running cargo trains from Guatemala City to Puerto Barrios. It has plans to get the line toward the Mexican border going again. Passenger service, however, is limited to only a high-class, expensive tourist train in Februaries.

Well, in my experience, where there are cargo trains, there is also clandestine passenger service. I will go in person and see if somehow I can ride with el pueblo—if, indeed, el pueblo can still ride the rails.

May 2003

I arrive in Quetzaltenango. For several weeks I try calling the telephone numbers for Ferrovías Guatemala I got from a website. No matter what time of day I call, one line is busy. At the other number, I receive a recorded message: The person you are calling is not available. Please hang up and try your call later.

In street gutters, I find spent phone cards with old-time photographs of Ferrocarriles de Guatemala. Card one of the series of six shows a steam locomotive. Card four, a woman waits next to a car in the station, a wicker suitcase at her side. On card six, a woman stands in the doorway of a back vestibule. The reverse of each tarjeta tells a bit of the history of this country’s railroad.

In an internet café, I see a large map of Guatemala. I stand there, on tiptoe, fighting the glare of glass, compiling a list of towns along that silver rail:

GUATEMALA CITY—San José del Golfo—Sanarate—Guastatoya—El Jícaro—San Cristóbal Acasaguatlán—Cabañas—Usumatlán—Zacapa—La Pepesca—Gualán—Natalia—La Libertad—Morales—La Ruidosa—Navajos—Cayuga—Picuatz—Tenedores—Veracruz—Entre Ríos—Piteros—PUERTO BARRIOS

Still, almost every day, at all hours, I call those numbers for Ferrovías Guatemala. The line is busy. The recording: The person you are calling is not available….

I also phone FEGUA. A woman tells me, “No, FEGUA has no cargo nor passenger service. When will there be regular passenger trains? I don’t know. Perhaps next year. Ferrovías Guatemala? Perhaps they do.”

I finally lay my game plan: The road from Cobán meets up with the Atlantic Highway at El Rancho, between Guastatoya and El Jícaro. To bypass the madness of Guatemala City, I will travel through the Cuchamatanes Mountains to Cobán and come down to El Rancho.

16 June 2003

From El Rancho

I search across these drylands

greened with scrubbrush

South of this highway

upon which I travel

Hoping to catch some sight of those

silver rails I so need

to ride to complete

this book

No still five years later

passenger service has

not resumed

But cargo has

from Guatemala City

to Puerto Barrios

A hope, a wish

… perhaps in vain …

& so to Zacapa I go

a town on that rail line

With my pockets full of

hope full of wishes

We are at Jícaro now—a town that map showed to be on the route. But I’ve yet to see the tracks. San Cristóbal Acasaguatlán, another town. Through the spaces, the vistas, between trees, bluffs, homes—no glint, no cut of rails. No bridge spanning that river. (I know the line swings quite south of the road for a while. Is this search in vain? I keep checking my list of towns along the way. Perhaps the tracks are on the other side of yonder río. (Is that the Motagua?) Usumatlán—three kilometers from the highway, the sign says. Perhaps this is a bit in vain—and I can’t hope to see it until we turn off this highway. The next town is Zacapa.

If this effort fails, I’ll try further up the line. I will keep hope until the end—if my courage to ask for a ride holds out.

I continue to peer across those lands. Three kilometers. Would that be at the foot of those now-mountains?

Part of my mind begins to argue: This is crazy. All you know is, there are cargo trains running. You have no idea how often. Yes, perhaps every day or two. Or perhaps once a week. Perhaps once a month.

Hope, hope—a wish and a prayer, another part of my mind responds.

I know the train exists, that it is once more being used. Wherever I’ve been in Latin America, freighters have taken passengers—clandestinely. Could this country be any different?

We are now at the turn-off for Zacapa, Río Hondo. Deep River—my river of hope runs deep. Let it not be dammed by discouragement, disillusionment or fear.

Yes, I’m mad, I tell that other part of my mind that continues to rant. I’m a Doña Quixote, with my faithful compañera Rocinante. Yes, I’m tilting at windmills in hopes that somehow, somehow this book will raise a call for the return of passenger services.

As soon as I write these words, we enter Zacapa. We pass a small plaza with a brick windmill—and Sancho Panza with Don Quixote.

My guidebook says there are inexpensive places to stay near the train station. That would put me just where I want to be—close enough to it should the opportunity arise to take a ride.

I stop into a shop to buy a juice—and to ask where the station is. The woman tells me, “No, it’s not safe there. There’s lots of robo.” Her right hand grasps at the air.

When I explain my quest, she walks from behind the counter. “No, during the day it is safe—even for a woman alone. At night it’s different.” She encourages me, “No, go there first and see. If not, you can return to the market area for a cheap place to stay—15 quetzales.”

I hop a combi. We pass the church and the being-renovated central plaza. Down streets, past stores and workshops, to the south edge of town. Soon I see the railyards with rotting wooden cars. On a nearer track a deep-blue and yellow engine faces the direction of Guatemala City. Attached to it are several container cars with the names of northern companies. Near the gate stands an armed guard, hands on rifle.

The stone station is marred by gang tagging. The orange, press-wood eave tiles sag in the humid heat. Some are missing, some have holes punched into them. A dulled plaque commemorates the first anniversary of the “gift” of the railroad from the International Railroad Company of Central America (aka United Fruit) to the Guatemalan government, in 1968. Deeply engraved on the front eave is FEGUA. But above the old ticket window is a new sign: FERROVÍAS GUATEMALA. The company whose one phone number was always busy, and the other number, “The person you are calling is not available. Please hang up and try your call later.”

Across the street is the ramshackle of an old, two-story turquoise building. The bottom half is adobe or concrete; the top half, wood. The empty windows stare at the station. Above the doors off the balcony one can still see the former room numbers. Without a doubt, this was one of the inexpensive hospedajes.

I check out the only hotel still operating, Posada de las Molina (the final “s” missing), Inn of the Mills. From the outside, it looks nice. An older woman sits in a screened porch in the plant-filled courtyard. She informs me it will costs 50 quetzales for the entire night. So this is where the lovers tryst, the women work their nights. Away from the center of town, away from the spying eyes of neighbors.

I return to the station and set my pack down on a tree planter. I call to the guard, “Is the station chief in?”

“What is your business?”

I introduce myself and explain my quest. He disappears around the corner and within seconds reappears. “You can come in and take photos if you like.”

“No, I don’t have a camera. My poems and stories are my photos to show people the journeys.”

He urges me to enter with my pack and points to a group of men talking on the back platform. “He’s over there.”

“The one in the red ballcap?” I refer to the older man.

“No, el joven.”

I walk up to the one who looks perhaps in his mid-thirties, tall and slim with short dark hair. Once more the introduction, the explanation—and then the question. “Do freight trains here, as in other countries, ever take passengers?”

No. But, yes, he could grant me an interview. He invites me into his stark, grey-metal-furnished office. An old wooden station clock on the wall is stopped at 8:25.

Douglas Aldana, the jefe de patio in Zacapa, spends the next hour or so talking with me about the new company, its fifty-year contract, and the challenges of bringing the trains back online. Getting the right-of-way clearance five years ago “took quite a bit of doing.” Hurricane Mitch has set them back. Cargo service is provided once more between Guatemala City and Puerto Barrios. Next will be the stretch to Tecún Umán. Yes, passenger service is in the master plans, but he has no idea what type of service it will be. I can probably get the information in Guatemala City.

Several times the phone rings. He lets his assistant answer the calls. The second time our conversation is interrupted. While he is gone, I study the list of stations he has photocopied for me—the altitude and milepost of each stop. When he returns, I say it must have been quite a ride, almost like a rollercoaster. Aldana’s eyes brighten, “Oh, yeh, it was quite a beautiful passage.” He suggests that if I go to Guatemala City, I could probably get special permission to ride on a cargo train.

When he was a kid, he never thought he would work for the railroad—though his father was a brequero (brakeman) and he had uncles on both sides that worked for it. “Ah, so you’re carrying on the family tradition.” “Sí,” he responds with a light laugh.

We go out onto the back platform. As I grab my Rocinante, I ask, “Where was the old waiting room?”

He leads me to the patio where I had first entered. “This was it.”

“Well, the benches are here. So there’s hope.” I shift the weight of my pack. “I have been waiting seven years to take a train here, without luck—and unfortunately I can’t wait another seven. But in fifty years, ay, perhaps there will be a train. We’ll both be retired. I’ll see you and say, Hey, Señor Aldana, let’s go for a ride to Puerto Barrios.”

He smiles and laughs.

“For me, train journeys are a good way to know a country,” I continue.

“Why’s that?”

“Because you have not only the vistas, and you are traveling slow enough to really see them, but—more importantly—you also have the community inside the train. And there are always three things that are the same with all journeys, no matter where.”

“Yes?”

“The whole human world has to stop for the passage of the train. The children wave. Dogs bark.”

“And it doesn’t matter where,” he says, looking thoughtful.

I glance over the railyards one last time. “In other places I’ve noticed people living in the old boxcars.”

“No, not here. We helped them find other places to stay. Plus that’s why we have an armed guard.” He motions towards the man who had let me in.

I flag down the first combi returning to town and watch the railyards disappear as we turn our back on them.

After dinner I resume my study of the list of stations, and my possible course of action. Of all the towns, the guidebook solely mentions Quiriguá. There is lodging there. Only five names appear in bold-faced, capital letters: Guatemala City, Rancho, Zacapa, Gualán and Puerto Barrios. What does it mean? The only staffed stations? (Then no use in going to Quiriguá.) Stations with workshops? (But Aldana said the only one was in Guatemala City.)

Damn, why didn’t I notice this before and ask him?

I have no idea where Gualán is, if it is accessible by road, if I could find a place to stay. All I know is that it is 21.9 miles, eight stops from here. Thirteen stops, 23 miles beyond, would be the next hope, Quiriguá—whose name sits on this page in front of me in plain type.

The next bold-faced, capital-letter station is Puerto Barrios. The end of the line.

I believe I have reached my last hope. Perhaps it is time to stow the lance and shield in the attic, put the horse out to pasture, and tell Sancho to go home to his wife and kids.

What would Don Quixote do in this case?

Wait fifty years, find Señor Aldana and say, “Well, shall we take a ride to Puerto Barrios?”

What should this Doña Quixote do?

It’s now nearing midnight. I’ve been reviewing my notes and realizing questions I’d forgotten, clarifications I need, points perhaps for this story. I’ve now a list of queries, in case I decide to return to the station come morning. If Aldana is willing to spend a bit more time with me. And I kick Doña Quixote out of the bed, who keeps repeating, “Perhaps, upon sleeping on it, he will have a change of heart.”

Just as I’m turning in, I hear a locomotive blast that lasts a minute. Then the rumble of freight cars in the distance.

About ten a.m. I arrive once more at the station. I can see Señor Aldana out on the back platform talking with some men in a pick-up truck. They begin unloading tools and parts. Finally he notices me standing by the former ticket window. He approaches. After we exchange the customary pleasantries, I ask if he might have a few minutes.

“We’re having problems with one of the locomotives. But if it’s only a few minutes, sure.” We enter his office.

My hunch about the bold-faced, capital-letter towns on the list is correct: the only staffed stations. Bananera is another, though it isn’t marked as such. The frequency is not a set schedule; only when necessary. As for the number of cars—the trains aren’t as long as in Mexico and other places, as the terrain won’t permit it.

We discuss the geography of the line. Aldana draws a map on the backside of the station list, showing its relation to the mountains, to the Río Motagua and the highway.

He suggests the best way to keep updated on when passenger service resumes is to e-mail or write the parent company, the Railroad Development Corporation of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It probably has a website.

Did a cargo train pass through last night? Yes, about 12:30 a.m.

As I leave Zacapa, traveling east on the highway, I keep an eye out for the glint of silver rails. I get off the bus at La Trinchera. Far across a field, I see a deep-blue and yellow locomotive.

I have called off the search for a train ride here. It would violate a basic principle of this book: to ride with the people. If, in this country, el pueblo isn’t allowed to ride the freight trains, then there isn’t a train for me to take. For me to ask special permission would make me an elite. It would be no better than taking a tourist train.

And I am sure Mr. Posner and his Railroad Development Corporation will continue for the next 44 years to tell the people and the government that passenger service “is in the master plans.” But as I have seen in many countries, when such service is put in the hands of private corporations, it disappears. No, it’s not important that it provides a safe, energy-efficient way to travel. Not important that it creates many jobs: the official workers within the train—as well as the ad-hoc vendors along the way, giving people in these impoverished communities some way to feed their families. Not important that it can provide a mode of transportation the poor can afford to take. The only thing that is important is, Does it make a profit?

We’d seen it happen in the US, Mexico.

And only when the government steps in, can the people be guaranteed this option of traveling.

Perhaps someday I can return to Zacapa and say, “Hey, Señor Aldana, let’s go for a ride to Puerto Barrios.”

story © 2004 Lorraine Caputo

REPRISE:

More than a decade later, are there passenger trains in Guatemala?

Still ideas float about to bring back passengers trains in Guatemala, from Tecún Umán on the Mexican border in the west to Puerto Barrios on the Caribbean coast. The latest plan was to be presented in early 2017 – but it appears this, too, has come to naught.

In the interim, you can visit the Museo de Ferrocarril in Guatemala City. This railroad museum opened in 2004 in the old train station in the capital city.

It would appear that I shall continue to be Doña Quixote.

About this Project

For three decades, I have searched for and taken passenger trains from Alaska to the Patagonia. To date, I have ridden over 100 trains – always local trains, no tourist ones – in almost all of the countries of the Americas. From these experiences, I have been composing a collection of poems and stories of the adventures.